RBA Indicators and Housing

Why It Matters

Australia’s housing market is highly sensitive to monetary policy, in fact one of the most sensitive within all OECD countries. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) adjusts the cash rate in response to economic data, and those decisions ripple quickly into mortgage costs, borrowing power, rents, and construction activity though are not specifically set around those parameters. In fact, they largely sit as byproducts to how the broader economy is performing, both domestically and internationally.

Key Indicators the RBA Watches

• Inflation (CPI, trimmed mean): Above the 2–3% target; rents remain a key driver as does new housing costs, the established market does not feature in the decision making process.

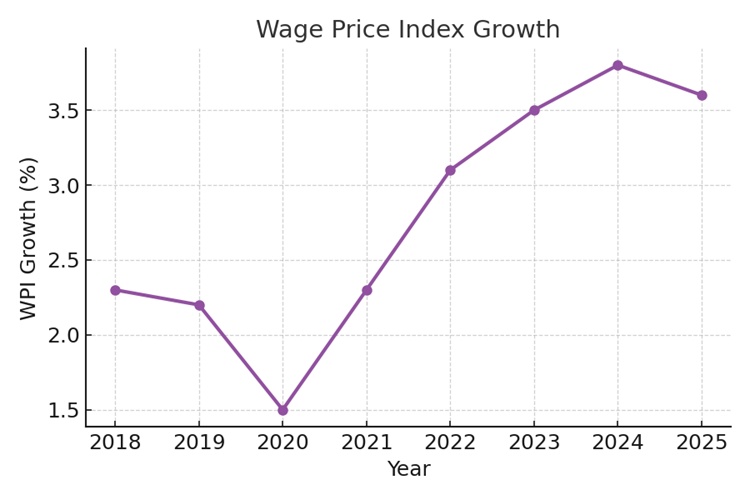

• Wage growth (WPI): Still near 3.8% y/y — strong enough to risk embedding inflation and a possibly a noose around productivity gains as is the next point.

• Unemployment: ~4.2% — low by historical standards; supports incomes but keeps pressure on services inflation. Running at full employment for a long period of time typically creates an environment where innovation slows.

• Housing credit growth: Slowed under higher rates; reflects tighter borrowing conditions. This is largely a reactive data point and one that is used to support arguments around affordability. Unfortunately this measure is at the end of the data cycle and does not explain how we got to this point. It is a largely a “good, bad or indifferent” indicator.

• Rental vacancy & expectations: Tight rental markets feed CPI and guide policy timing. This data point should also be used in conjunction with the supply, particularly starts rather than relying on approvals alone.

Current Policy Setting

• The RBA is holding the cash rate at restrictive levels until it sees clearer progress toward the 2–3% inflation band. Whilst inflation was anticipated to increase in 2026, the latest data creates concern that there has been a pull forward to these expectations.

• Housing‑related inflation and wage growth are slowing the pace at which it can begin easing particularly when the employment conditions reflect the definition of being full, ie an unemployment rate lower than 5.0%.

Implications for Housing

• Borrowers: Mortgage rates likely stay higher for longer; serviceability remains tight, and household saving will become the focus again rather than spending. This will likely slow some aspects of the economy and have a dampening effect on inflation. It will however take time.

• Developers: Elevated financing and construction costs continue to restrain new supply which remains highly inflationary. With continued tightness in trade based labour, increasing number of industrial disputes and days lost as a result of this, this sector will struggle and likely pivot to infrastructure projects underwritten by Councils and government at profit margins that private developers find difficult to compete with. Land remains in short supply which is driving sales rates in the urban fringes at or at near record levels. The rate of sale only seems to be limited by the time it takes to release stages to the market in many capital cities. Increases to prices in stage releases of circa 5% is not uncommon.

• Investors & policymakers: Rental market tightness sustains upward pressure on rents and CPI, influencing the rate path. Investors typically have greater access to capital making competition with first home buyers this one of this cohorts’ biggest challenges/competitors.

Strategic Takeaways

1. Watch quarterly CPI — especially the housing and rent components.

2. Monitor labour‑market data and WPI for signs that wage‑driven inflation is easing.

3. Track credit growth as an early signal of shifts in demand and price momentum.

4. Recognise that supply‑side constraints (planning, labour, materials) mean lower rates alone won’t quickly solve affordability for buyers or tenants.

Matthew Gross | Director | Mgross@nprco.com.au