House Prices, Interest Rates and Forecasts. Part 1

The headlines are again generating stories around how the residential property market will correct substantially in 2023 with the rot starting to set in, in 2022.These are from the same banks that forecast significant asset value corrections as a result of the pandemic…the polar opposite has occurred.

Not for one minute is the author suggesting that the current market conditions and escalation in pricing is sustainable, it isn’t. But because something isn’t sustainable, conversely that doesn’t mean that there has to be a significant correction either. The issues around the sustainability or more realistically, financial viability of debt servicing is a very simple way of looking at what is a complex and systemic problem across almost every level of government, where ultimately the poor punter looking to buy a home is lumped with all of it. There should be a disillusionment index…

Before we consider any other point, debt serviceability is a very significant part of the residential property sector, however it is reactive, not causal. It makes assumptions around who can afford what and how Australian’s manage their household finances. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority do an incredible job of it, hence the very low foreclosure rates.

The second point is that the Reserve Bank has continued to reiterate that it is in no hurry to lift interest rates. It wants to see sustainable inflationary data within the 2% to 3% band that it believes is ideal. It wants to see businesses expanding, profits improving to increase resilience and for this to work through to increased weekly wages. If this happens, there will be more money in the economy which runs counterproductive to the argument that household balance sheets will collapse creating a shortfall in the capacity to meet repayments. In very basic terms, interest rates go up when the economy is healthy, they come down when it needs stimulus.

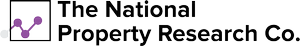

The last time APRA stepped into the market, it was to cool the investment property sector which was arguably more timely for Melbourne and Sydney than it was Brisbane, Perth or Adelaide for that matter.

As a result, the Sydney market cooled from a peak of $1.05 Million in June 2017 to $875,000 in March 2019. So corrections are real, but this was also a period in time where inflation was declining, the economy was stalling and the 2019 Federal Election turned out to be particularly toxic, divisive and confidence sapping…which may in fact be what Australia gets again in 2022. The RBA cash rate which was already at record lows of 1.5% in 2017 and actually halved to 0.75% by the end of 2019. These were pre-covid economic conditions whereby the RBA was using its only lever to stimulate the economy. So property prices actually fell on the back of declining interest rates which is the opposite of the current argument doing the rounds.

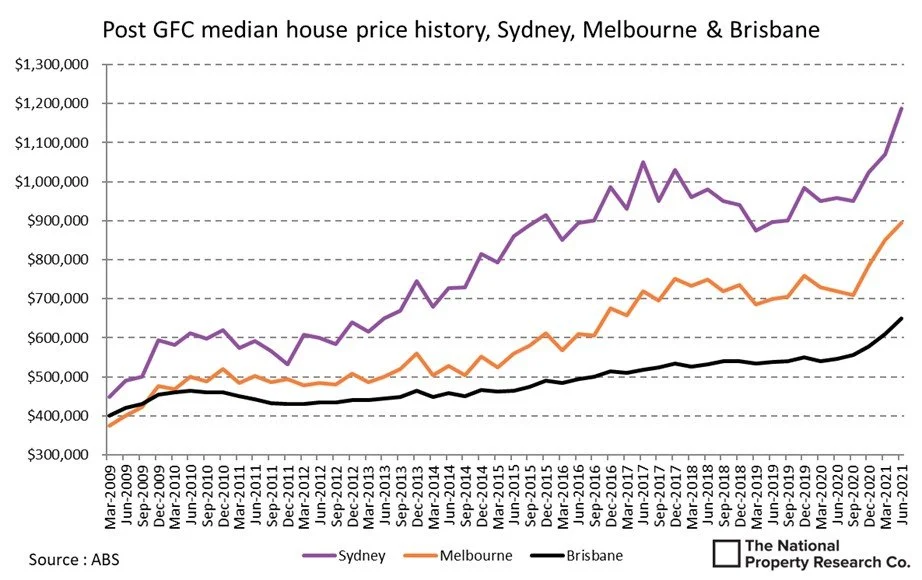

If you were to look at the relationship between prices and the RBA cash rate, the reality is the correlation is very weak, meaning there is significantly more at play than just interest rates. The strongest correlation between prices and interest rates among the east coast capitals is Sydney, which diminishes significantly down to Brisbane. If interest rates were the great predictor of value appreciation and depreciation, then predicting cycles would be simple. Clearly this is not the case otherwise developers would never go broke; banks would never foreclose and Government would get their supply and demand equations considerably more balanced.

A final point on residential prices and interest rates which should really be a “duh” moment for anyone involved in property is this; interest rates are set nationally, not regionally or even capital city specifically. There is probably a very good argument that they should be set that way, but that is a discussion for another day. The very simple point is that whilst interest rates are a national setting, capital city and regional real estate markets operate at different speeds and have different cycles, both in terms of growth/decline and duration. That point alone should cast doubt on the massively, overly-simplistic notion of interest rates determining prices.

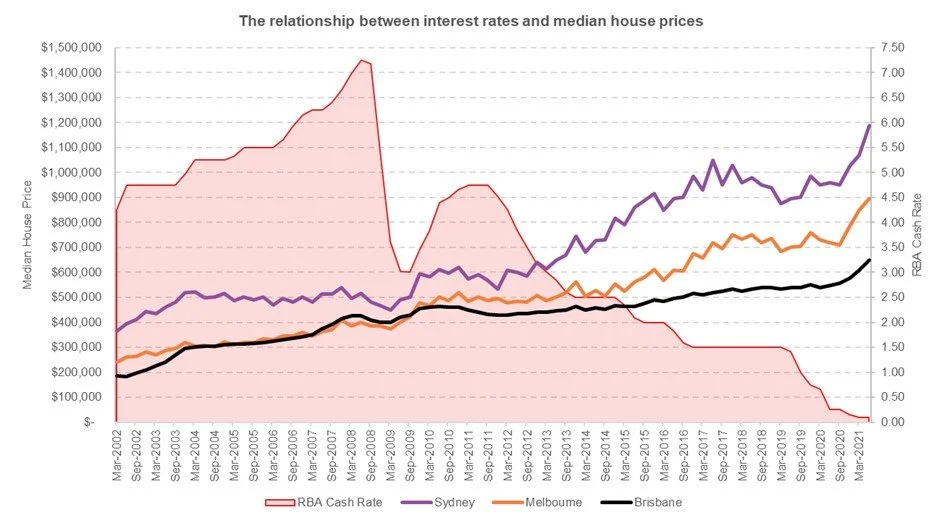

Whilst all of the focus at present is on median house prices, in some respects the more important economic indicator is often the volume of sales, as the flow through to the broader economy has a greater impact on job creation. Whilst there was minimal correlation between interest rates and price fluctuation, there is virtually no correlation between the volume of house sales and the movement of interest rates. This should continue to dispel the urban myth that house prices ebb and flow with interest rates. If the interest rate theory held any credibility, the volume of sales should fall with interest rates (lack of confidence) and rise with interest rates (growing confidence). The graph below demonstrates that this is not how the residential market operates.

This leads the reader to the pending release of Part II of this newsletter - where the author will demonstrate succinctly why the current forecast of property prices to the negative are highly problematic…and it has very little to do with interest rates.

Matthew Gross | Director | mgross@nprco.com.au